|

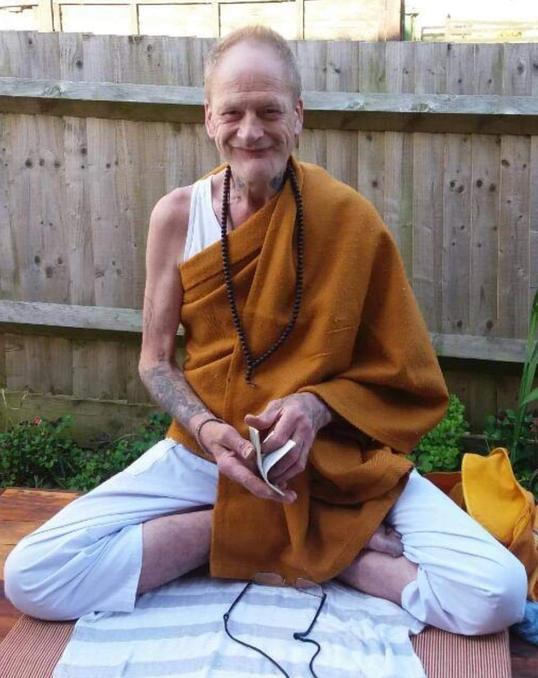

Following a lot of tests and monitoring I found out more yesterday more about the heart condition that I have been suffering from the last few years and realised that it carries a high risk of stroke. This was quite a big thing for me to discover. In my professional life before I ordained as a monk I was a psychologist and physiotherapist specialising most of all in the rehabilitation of stroke patients. Although, as a practitioner of the Dhamma, I was continually reflecting that I could end up in the same situation as my patients, it was not until yesterday that I felt I had crossed the subtle divide between us. I find myself looking back at my patients with renewed compassion and respect for the way they coped with their situation and I feel so very human today.

I had the same feeling twenty years ago after a severe back injury when I realised how much pain my many back patients must have experienced. This time, however, the bond feels deeper still. We are truly brothers and sisters in the face of death. Deeper still, to so ground the mind in the body is ground too for the process of liberation. The way out is in. To enter the body fully with a heart wrapped in the loving space of the breath and to see its reality is the way to a true and complete freedom from suffering. The stress of the world, or of the sickness, may remain then on the surface but it does not fully penetrate the heart. We remain safe inside. Once I sought the love of the young lady Burning consumed and consuming Now I seek the love of old men Cool saved in the grave A different kind of love I have been thinking lately what I might say were the first origins of my own, individual spiritual path. I was brought up a Christian and admired my devout parents and grandparents for their goodness when I was child but I found the Christian teachings hard to understand or believe in. Then my first ever introduction to Asian spirituality came when I was thirteen years old. I used to go with a friend to a local park to play tennis. There were a number of public tennis courts in the park. My friend and I had booked a court for three o'clock and we were a little early. There were some benches where people waited for their turn and I found myself sitting next to an elderly lady who was also waiting, dressed in her tennis outfit and carrying her racket. I was immediately fascinated by the fact that such a thin, rather frail looking old lady was still able to play tennis at all. I said, 'hello'. I have a vague memory of her replying with a polite, rather refined, 'good afternoon'. I remember nothing of the rest of our conversation which was unremarkable, it was simply in the manner of the 'do you come here often, isn't it a nice day' variety. I only remember being completely captivated by the look in her eyes. Her gaze was very bright and sharp and there was a depth there also which held a mysterious quality. She asked me if I would like a copy of a book that she had translated with a friend of hers from the Chinese. I readily accepted. She proudly signed it for me and we parted for the courts. As I played tennis with my friend I occasionally looked over at the old lady in the court next to ours. She was playing with a younger woman and was remarkably quick and agile for her age. When I left the park that day I did not think to say 'goodbye'. I thought I would see her again but I never did. The book she had given me was a copy of the 'Tao Te Ching' by Lao Tsu. I have treasured this little book all my life, returning to it over and over again. It led me to take up T'ai Chi, my first meditation practice, in my early twenties. Still it remains a reference especially with regard to my engaged spiritual life picturing as it does, in a remarkably tangible and dynamic way, the relationship between conventional and ultimate reality. It is a remarkable teaching on how to flow with life. It is remarkable to me now how much such a brief encounter with someone could end up profoundly changing the life of another person and underlines to me how much potential there is in meeting children of such an impressionable age. I sometimes think of her when I meet with children myself hoping I may be able to influence someone else the way she influenced me. I can remember her face to this day. In one way this was why I found myself immediately converting to Buddhism when I first heard about it four years later in a religious education class. I could see that Buddhism made sense and thought I could be good without needing to believe in anything – I could investigate the truth for myself in my own time, I thought. But there was also something in me that trusted the mysterious depth and obvious happiness and vitality of that old lady, Margaret Ault. There was something, especially in the latter qualities, that I simply could not doubt. So I remember Margaret with great affection and gratitude. There is also nothing like acknowledging the help we have received from others on the path to help us to be humble, avoid conceit and make us willing to do the work necessary to try to help others in return. I practised for about twenty years in lay life before I ordained, at age 36. The factors I found most important in order to maintain my practice as a lay person was the job I was doing and the company I was keeping.

In terms of my work, I chose to become a physiotherapist in order to be able to investigate body and mind and also to try to help people. So in other words my knowledge was always aimed at practical application; I saw the dangers of abstract theory and didn't get lost in it. I also specialised in my work and dug deeper as much as I could. I found that if I was doing the same thing over and over or considering the same thing in more and more depth, this was less exciting than seeking new challenges, but much more conducive to meditation. Moreover I worked a lot with the elderly to try to slow myself down and also found this very sobering. Today, looking back on these days, I think I would also have done a mindfulness course to take the practice even more into the workplace. Another aspect was that in my work I was more and more faced by the fact that some people had huge problems and suffered very little, these were the ones with the strength of mind; others had small problems but suffered a lot, these were the ones without such strength. So working with the mind and teaching this to others made more sense than trying to solve their problems in themselves. And all I had learned about body and mind along the way of my career was to be equally of value in my monastic life, this time in the supporting role rather than in the lead. In terms of company I sought out any kind of group I could find connected to eastern spirituality – yoga and T'ai Chi classes for example, and I developed a social life with the people I met there. The formal meditation practice was not so important to me at this time, it was a support to mindfulness and a way of relaxing, not much more than that. And T'ai Chi at that time was a very helpful aid to mindfulness of the body and also integrated well into my daily life. It took me years to appreciate how deep it could all actually go. Eventually I chose the monastic form as a way of committing myself more fully to the meditation practice. Now I can regret not having got more into the meditation a bit earlier, but I was very energetic in my youth. I also look back and realise that I did help other people, I feel good about that, and it was all sowing the seeds for the deeper investigation of Dhamma that ensued. We have to start from where we are and try to bring that into our Dhamma path. When I became an anagārika I had taken a sabbatical from my research PhD in psychology at Southampton University to spend a year at Chithurst monastery. All my work colleagues thought I was crazy, my career was really taking off. I had spent seven years training first as a psychologist and then added on physiotherapy with the aim of doing research in the area of neurological rehabilitation. Yet, all along my personal agenda, as a practising Buddhist, was to develop my contemplation of body and mind. I was not really sure what to expect from monastic life but for the first few weeks it was just good to give my brain a rest and do the simple work of cooking and driving and so on.

Then one night, out of the blue, I had an extremely lucid dream which was to change the course of my life. I dreamt that I was rushing around the wards at the hospital, as I had been for so many years – but instead of patients in the beds there were just organs. In one bed a liver, in another lungs, in another a pile of intestines. I had no idea what to do. The situation seemed completely hopeless. I just kept running around saying to myself, “What am I going to do, what am I going to do?” When I woke up I sat up in bed and my first thought was, “Oh no, all that work!” I realised that my hospital career was at an end, and here I am still in a monastery twenty-five years later with no thoughts of going back. Looking back I can think that perhaps the taste of freedom, of letting go, I had experienced a few years before after a trip to the morgue had gone deeper than I had thought. It was February, 2012. It had been a cold winter that year to be on retreat. I had been meditating a lot and exercising as well to keep myself going. Then one day I heard that there was a funeral approaching in the monastery and the body had arrived and was laid to rest in the temple. As was my usual practice I went to see and to practice mettā meditation for the deceased. When I arrived I realized that I had met the man a few times. He was well known as an exercise fanatic, there were pictures of him in local newspapers on display were he was doing various extreme things for charity and so on. There had been, I had heard, some strange events since his death. Apparently the Buddha figure in his home where his body had previously been had mysteriously fallen from the shrine and broken. The same had then happened in the temple. I also knew that he had had a slow and difficult passing with some awful neurological condition. My mind came to wonder whether this man had lost faith through all that and then found some way to show it after he had died. I returned to my hut in the forest to continue practising and for a moment felt despondent. I thought of all the exercise I was doing and of the dead man and found myself thinking, with a big sigh, “Oh, what’s the use.” After all the meditation and contemplation of the body and death I had been engaged in over the last months, something in me immediately found that thought funny, but as soon as I smiled at myself a massive wave of bliss took over my mind completely. My body was filled with light and an unbelievable rapture. This ecstatic feeling lasted a few minutes, I think, I am not sure and then I had a very clear vision of my teacher, Ajahn Anan, smiling very broadly. Then I surprised myself with another thought, “I wonder if that means he feels like that all the time.” Two years later I was in Thailand and finally had the chance to ask Ajahn Anan about this experience. I wanted to know if he really did feel like that all the time. He said yes. I was and am still completely amazed by that. He then leant forward and with an extremely penetrating look in his eyes he said, “Kalyano, that’s the highest.” From that time to this I have kept returning my mind to that. This is a difficult practice, I need all the encouragement I can get. Aj. Kalyāno March 20, 2014 One time my mother came to stay with me at Amaravati monastery in England. I had returned home from abroad because she was going blind and needed more support from me and my brother. It was early summer and the bluebells were out in the woods opposite the main gate. I took her over one afternoon in a wheelchair and left her to enjoy the scene with the little sight she had left. She remembers it as a precious day, and as her last memory of seeing bluebells. One of the monks at Amaravati called her the other day. She urged him to go to that piece of forest and enjoy the bluebells in her place as an act of remembrance. She asked him to pick one of the bluebells and put it on the monastery shrine as an act of veneration. She could practice sympathetic joy (muditā) for him as he did so, she said. In doing so she enjoyed those bluebells again with a heart as pure as snow and renewed her hope in this time of crisis. I offer this for your reflection Ajahn Kalyāno http://www.openthesky.co.uk It was approaching dusk on a cold winters day at the monastery. The sky was pale grey and there was a stillness to the air. We were on a meditation retreat and the community were gathering for the four o’clock meditation sitting. I was just approaching the house when I spotted a very large bird sitting on a branch just at the edge of the lawn. I approached. Much to my amazement the bird was a very large owl, by far the biggest I had ever seen and as grey as the sky. It was looking towards me with a piercing yet open gaze. It blinked and I froze on the spot. Owls had always been special to me ever since my father had read Winnie the Pooh to me as a very young boy. To me they had become a symbol of wisdom. The atmosphere on this winter’s afternoon was such that this great bird seemed to embody this quality like never before – my mind brightened and fell completely silent. I felt somehow at one with nature and with this place. In the moment the scene appeared to me as though it were a lucid dream, luminous and still yet lacking none of its sense of reality, my hands were cold. Anagārika Mischa was approaching along the path towards me, I beckoned to him to slow down, pointing as the owl retreated to a tree a little further back. I gasped at its size and at its slow, silent flight. As I spread mettā to the great bird, it turned its head towards me and flew a little closer. By this time I was completely enchanted. I felt as though I was immersed in a fairy tale. I would not have been surprised if the bird had spoken. I turned to Mischa, “I think something special must have happened,” I said, much to my own surprise. The words just seeming to tumble out of my mouth on their own. The owl took flight, passing behind the house and into the forest, out of sight. I repeated to Mischa, “I think something special must have happened. I never say such things but there is something auspicious about this.” I returned to my hut and did not join the meditation. I stared through the window at the glorious, crimson sunset. I couldn’t stop wondering what might have happened. Later that evening I received a mail from a very generous supporter. He had decided to sponsor a sala to be built on the hill behind the house. I was stunned, all I could think of was the owl. I realised it had flown right in the direction of our proposed sala site. I felt a little overwhelmed. I could not resist writing back immediately, “Did anything happen at your end around 4 p.m.?” “That’s about when I made the decision,” he replied. So it seems as though that winter day something special had happened. I hope one day someone will give a very wise Dhamma talk in the new sala, worthy of such a message and such a messenger if that is what it was. Then it will seem as though the Dhamma had arrived in Norway in a very special way, in a way perhaps acknowledged somehow by nature itself and perhaps we will carve an image of the owl to adorn the new sala in the new style of ‘Norse Theravada’. Or perhaps we will do that anyway. Video versionTwo years ago my heart was effected by a flu virus. I don't think I will ever forget lying in the ambulance all wired up to the heart monitor. The paramedic kept talking to me all the way, “Any pain?” “What day is it today?”

I knew the situation; I was at risk of a heart attack or a stroke, that was the reason for the continuous checking. I just kept looking at the skin of my bare chest with all the ECG stickers all over it and surprisingly I felt completely unconcerned. This was so clearly a result of the practice but it still really surprised me that my contemplation of the body had gone as deep as that. I really felt quite happy. I was remembering how a few days ago I had been feeling stressed over monastery administrative stuff and wondering if my practice was starting to weaken with all my responsibilities. I was reassured that underneath I was still alright. I still had my refuge when it really mattered. |

Categories

All

|

Open The Sky - Reflective and creative work by Ajahn Kalyano