|

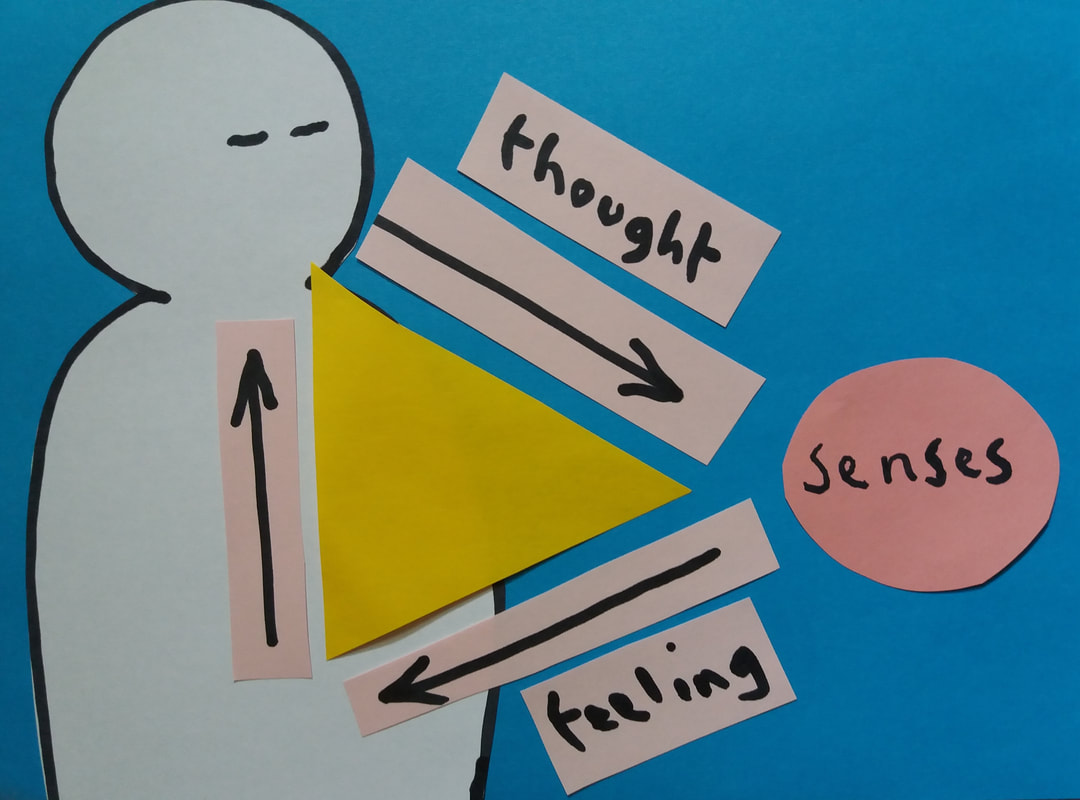

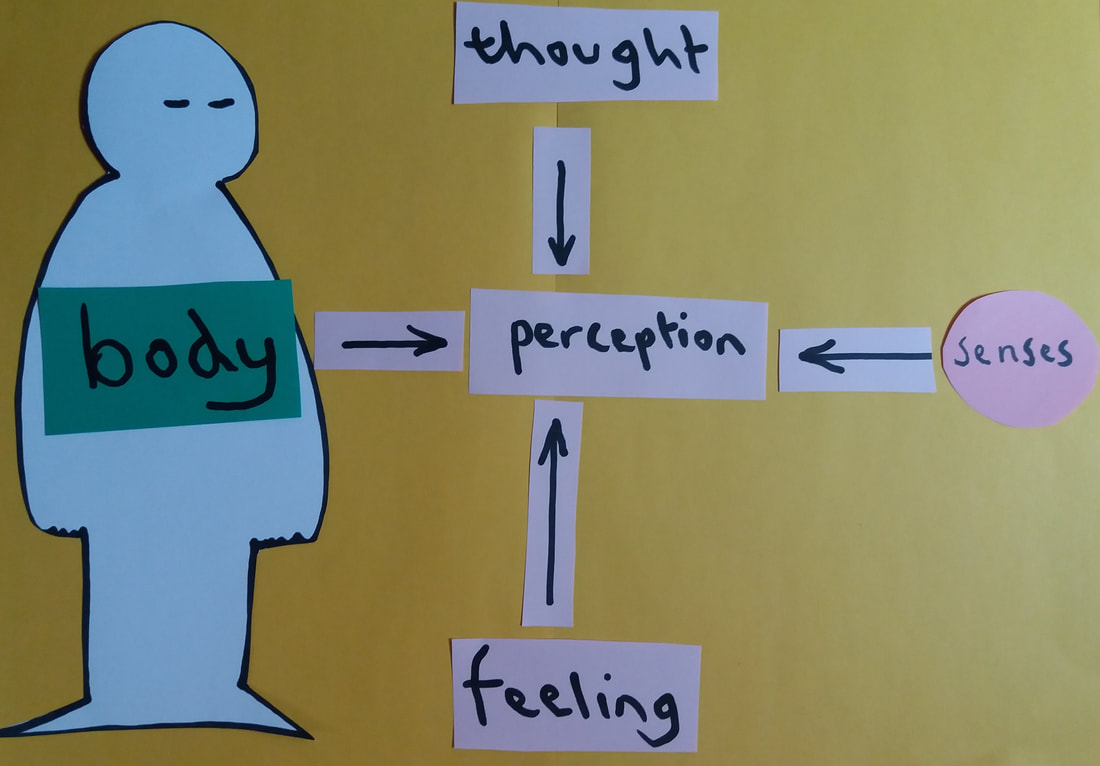

During the autumn of 2020, Ajahn Kalyano was so kind as to offer qigong lessons to the community living at Lokuttara Vihara in Norway. During this period of lessons and occasional discussions we gathered some of the information and the following paper and instructional video is the result. As qigong is also reported to have potentially positive effects on the immune system and increasing the lung capacity, it is our hope that by creating this paper that we can introduce more people to this interesting practice so that they may increase their resilience in these times of crisis. Pdf documentAccompanying videoPlease read the pdf document before attempting the movements. This video is intended as a supplement to the paper, and does not contain sufficient instructions to take up the practice. --------------------------------------------- This is part one of a series of two articles on Ch'i Kung. 1. Buddhist Ch'i Kung - The practical side 2. Stillness in Movement - The meditative side --------------------------------------------- Introduction The Taoists believe that ch'i is the ultimate energy from which the entire universe and the essence of all life is derived – beyond the limits of time and space. The stronger the flow of ch'i, the stronger the life energy. This ch'i is something that is experienced in the body as warmth or inner light, the latter being the stronger. There is a clear relationship in such experience between ch'i and space. They seem to appear together in the mind, a sense of space has a certain energy about it. The Chinese believe that because there is ch'i so there is space, space is formed by and subsequently filled by ch'i. A Buddhist view of the same phenomena would be that because there is space (in the mind) there is ch'i. In Buddhist understanding this kind of energy is related to samādhi, emptiness of mind. It is a mental rather than a physical phenomena, or at least it is related to thought and feeling. (Although the Buddhist view of the mind is that it is far greater than just these.) Emptiness, as the absence of negative emotion, is already a healing force. This is important because we then realise that our state of mind is a crucial factor in the generation of or protection of ch'i and we see the value of keeping moral precepts to protect our minds. My understanding of an example from history of the result of the dialogue that ensued between these two views is that a 'mind only' school of Taoist philosophy was born that acknowledged the Buddhist view. (For my take on this 'mind only' view and its connection with the Buddha's teaching see my accompanying article 'The Creation'), but if you are intent on the practice, as you should be if you are starting out, please continue and come back to the metaphysics when your practice shows results that you need to integrate into your world view. Stances The static stances in Ch'i Kung are our chance to connect with the stillness of the space element. Holding a ball of awareness in front of us, contained within the arms is where we first become aware of an awareness outside of the body – a brightness to the space. Static stances are also a way of enhancing our awareness of movement. We hold a position until the strength muscles of the body fatigue out and the postural muscles take over. These deeper muscles have a much more refined control over or limbs than the strength muscles. In particular they control the fine rotational movements at the joints. These rotational patterns of movement furthermore work to enhance our three dimensional image of the body in space, aiding the formation of a picture of the body in the mind. We also find we can move in a much more relaxed way in which tension is not induced. There is a sense of effort when we move with the strength muscles, but there is no such sense when the postural muscles are working. Hence it is possible to keep the body upright with absolutely no sense of effort whatsoever, as though our limbs are floating. Balance and posture Normal movement is usually also controlled outside our conscious control. An intention is set to move and the body is directed at its goal. The goal is the conscious aspect and our sense for the body is merely background and feedback as to progress. So the conscious control of movement is unusual. Even people with refined bodily skills can lack body awareness. This is developed far more in movement where there is no goal in mind – slow, relaxed movement. Attention is directed towards the body using the hands. When the hand passes over certain parts of the body there can be a sense of recognition, a feeling that tells us that the hand is there, stronger when the hand is close, weaker when it is further away. Then, as we move we can keep that feeling of connection between the hand and that point. We can ask ourselves, 'how does my body know where my hand is'. The most important points are the point just below the navel and the point in the middle of the chest. These are the centre of gravity of the whole body – standing; and the upper part of the body – sitting, respectively. As we become more aware of these points as we move, then we become aware of gravity and have an enhanced sense of balance and posture – and an enhanced proprioceptive sense. It is hard to describe the sense of the body in space; we just know where our limbs are. Actually we do have little receptors in our joints that tell our minds the exact angle at each joint. So this proprioceptive sense is not through a conscious sensation but comes to us in another way which is independent of physical sensations. This makes it an integral part of our body image. There is a connection here also with awareness of the breathing process. Similar receptors tell us of the movements of our chest and therefore the size of the breath we take. In the Buddha's teaching on mindfulness of breathing, the word used to know whether we take a long or short breath (pajānāti) is a word usually reserved for the knowing of high realisation, not of such mundane affairs. I believe the use of this word is to indicate the importance of this knowing for realisation – that knowing the body in this way is knowing the Dhamma, the Dhamma is the body, or more precisely the body image formed through mindfulness. The body image arises in the mind when the effort is not too tight or too loose. Our awareness needs to be relaxed and open yet held to stay with its object. Then we find a part of the body to focus on in more detail. When one part reveals itself in detail then the rest will tend to come. So there is no need to try to imagine the whole body. In fact imagination is not necessary at all. An image will arise naturally in time. (Moreover, unless samādhi is highly developed, the body image will be just a mental image of the surface of the body. This is fine however.) Fully developed mindfulness of the body As we develop a sense of the weight of the body or its 'earth element' we discover the interesting fact that this sense of weight varies – as we become aware of the space element the weight lightens and can even disappear altogether. We feel extraordinarily light. Now we begin to see how subjective our experience of the body is, we are shifting the objective physical impression of it. Gradually this new impression becomes an image in the mind. Instead of sensing our mind in our body we have made a shift to experiencing the body in the open, calm mind. In the Buddha's teaching the theory is that mindfulness of the body, a full realistic body image comes around through the awareness of posture, movement and elements. Modern cognitive psychology shows us that such a body image is different, a more discrete image than that formed by sensations. So in the mind these two representations of the body are separate and can be experienced separately at different times. What is perhaps surprising is that experience of the neutral image is far more pleasant than the felt experience. The image effects our feelings radically, cooling them down. This is also surprisingly pleasant and we can begin to lose our taste for the more intense feelings of sensuality. Hence these exercises take us naturally in a spiritual direction. The breath and movement of ch'i The pattern of the movement of ch'i is the pattern in which the space element is revealed through mindfulness of breathing, the space being the stillness through which the air is moving. We will only see or sense this pattern going in a particular direction, not another. It is in the reverse direction to the pattern of the feeling of the breath itself. This is something we open up to – it is not a matter of creating this with the imagination. We can be deceived by the imagination. In the Chinese practice, initially the mind leads the energy but through repetition then the energy leads. But it is merely that the memory starts to lead and the mind in the present follows to reinforce that memory. This creates the illusion of something real that we follow. This is a fake. At best we can be looking for something that others have seen in their body through deep meditation and if we don't find it we are creating what we do not find. This is akin to superstition and imagination replacing genuine psychic ability. We can also see in our experience that the emptiness of the mind can be extended beyond the body. We can see the brightness of mind move out from the body as we direct it there. We can leave this as a mystery for now and come back to explain this later. This emptiness can therefore potentially resolve problems in others. So, if we are looking for magic it lies in this emptiness. This magic is a separate reality from that of the things of nature, just as space is separate from form, so it does not confuse things – and magic and science can go together, they do not contradict each other. The practice of samādhi empties the mind and fully accesses this magic. I offer this for your reflection, Ajahn Kalyāno http://www.openthesky.co.uk/ --------------------------------------------- This is part one of a series of two articles on Ch'i Kung. 1. Buddhist Ch'i Kung - The practical side 2. Stillness in Movement - The meditative side ---------------------------------------------  --------------------------------------------- This is part two of a series of two articles on Ch'i Kung. 1. Buddhist Ch'i Kung - The practical side 2. Stillness in Movement - The meditative side --------------------------------------------- What you are currently reading is a simplified adaption of the introduction to Ajahn Kalyāno’s forthcoming book Realistic Virtue. The essence of it is the influence mindfulness established on the body exercises on our relationship with our thoughts and feelings. *** It is possible through meditation to unify our experience of life, of our mind and body and the world we live in completely within an open awareness, a sense of space. Within this space it is then possible for the different elements of our experience, the body, thoughts and feelings to find their natural place and dynamic: The essence of the mind can step back and find its centre in the body, thus we find a safe refuge. The content of our minds, thoughts and emotions appear in front of the body becoming a clear medium through which we experience the world. Physical feeling and mental or emotional feeling thus separate. We see movement within the stillness of space and we can stay with the space. Our inner world, which we realise was a product of our relation to the outer world, goes back to its source leaving the inner mind empty and bright. We do not identify with any particular part of the experience. Our experience becomes simply one of open ‘awareness’ in which all phenomena, real objects and also mind-made objects, thought and feelings, come together and yet are not confused with each other. We see the movements of our minds within this space, as well as the content. Let us represent this space, this field of information, like this, mapping it onto our subjective experience. As we centre the mind within the body we look out at the world through the window of our thoughts and their formative perceptions that are the central axis of the mind. We thus also see clearly and separately what we are projecting on to the world and what information comes back to us – the cause and effect of our mental activity. This can become a conscious process as we place our states of mind back into or onto the world of their origin. Then, very simply, we can be honestly asking: “What is it I am averse to here?” “What is it I am attracted to?” From a place of spiritual refuge our minds can take a fresh look. We can end up reviewing the priorities of our lives and at the same time see how and where to follow these priorities – a clear experience of body and mind taking us to a clear present-moment view of the world we live in and our relationship to it. We have a clear, broad, open and unified awareness of life. Finally to put all this in its ultimate perspective the highest spirituality lies in relinquishing ourselves rather than in self development. It is the happiness of the altruist. It is also the happiness of the wise who, seeing clearly, are freed from their attachment to the impermanent, conditioned world including this illusion we call ourselves. Ultimately this path goes beyond all kinds of being to the realisation of a state of pure truth or knowing. So the true path lies not in a refinement of being (not even in being energy rather than matter) but in a refinement of knowing and seeing which covers all aspects of our experience. The refinement of our minds through meditation is aimed at this. I offer this for your reflection, Ajahn Kalyāno https://www.openthesky.co.uk ------------------------------

For an example of my personal experience of the practice of stillness in movement as Chi Kung, please see pages 14-15 of the book Virtue and Reality. --------------------------------------------- This is part two of a series of two articles on Ch'i Kung. 1. Buddhist Ch'i Kung - The practical side 2. Stillness in Movement - The meditative side --------------------------------------------- |

Categories

All

|

Open The Sky - Reflective and creative work by Ajahn Kalyano