|

There have been so many instances throughout history of religion going astray that it is understandable that people turn away from religion toward a freer spirituality. What can be lost in this transition, however, is the sense of something timeless that comes from a long history or tradition and the social cohesion this creates. The prayers, rites and rituals can have their place and yet for a religion to remain alive the true meaning of such acts must be borne continually in mind.

This is part of the work of religion that keeps it pure. The temptation these days is to turn our backs on religion rather than taking our part in maintaining this purity, but then we end up on a lonely journey. Rather than entering into the positive karmic stream of a group, we are isolated. In my own case I vastly under-estimated the potential of such group karma – the karma of a culture or tradition. I took for granted much of the positive karma of my own culture, karma that created a degree of social justice and welfare. The system was so anonymous it was hard for the benevolence of the society to really touch the heart. Religion can serve to make this bridge between the personal and the universal, defining our relationship to the whole in a skilful way. Then our religion will not be a source of conflict but of peace; not a source of empty solace but a real refuge. When we come back home from a peaceful walk in the forest and we begin to feel stressed again we can begin to question, ‘do I really need all this stuff?’ In my family it was a tradition to get together sometimes and have a big purge of the house to get rid of anything we did not need or want anymore and create some space. The cupboards and drawers would start to overflow with stuff and we would know it was time. It was always difficult at the beginning. There would be so many memories associated with everything,

‘Aunty Dorrie gave us this’ or ‘do you remember the day...’ As the purge went on, however, we would begin to see the space and order we were creating and start to enjoy the process. There was a great relief to being free of all the clutter. If we let go of things more and more this sense of relief, of freedom can become paramount and we get bolder and bolder in what we get rid of or give away. We can start to incline towards simplicity, our living room goes Zen. We start painting everything white. We build a tree house in the garden. We delete our Facebook account. We look at the stars at night. We have space in our life. We are happy in a completely new way. This is the joy of renunciation. It goes a very, very long way… It was a fine autumn morning in September when, arising a little stiffly, I realised I needed to take my body for a walk. I calmly set off, rubbing the sleep from my eyes with a little gentle happiness, nothing special. Yet setting off through the forest with a mellow heart I found myself wishing a good morning to all the trees and other inhabitants. To my surprise that morning to calmly and sincerely say ‘hello’ to nature brought the experience alive in a brand new way - I did not just see a lot of pretty shapes and colours, acknowledging all the living beings out there in this simple way I naturally felt full of love and respect. I congratulated the trees for growing well this year and the ants for building their hill even higher. Likewise my concern for nature felt more personal, more human, coming from an immediate and realistic perspective. My love felt safe beginning at the heart and not going straight to my head. My love was constructive and open, active not passive, not full of opinions and expectations. I was not thinking that things should be this way or that and starting to worry. I was not wanting anything. I was simply ready to help. I helped a beetle across the road. I ended up taking a long walk all the way to the ocean. Paddling in the gentle breakers the water was cool. The sand moulded to my feet and I was gradually invited by the body back to the cool ground of the heart for a well-deserved rest. It had been a memorable day. And today, going about my business, I still find that I do not forget my friends in the forest and act irresponsibly. I speak up for my friends when the opportunity arises. I feel good inside where it really matters. And all this comes so naturally and simply just from remembering to say ‘hello’ to nature, straight from the heart. Video versionThis is part 3 of the "Nature Series". 1. A walk in nature 2. Finding our place in nature 3. Hello nature 4. Our goodbye nature 5. It's never too late to love the world 6. True love for the world Meditation is the purpose of Buddhist monasteries and monastic life. All the rules are there to help the meditator to focus and protect their minds. The rules are not statements of right or wrong but of that which is not conducive to higher meditation. For example, sex is not considered wrong or sinful in any way. It also becomes obvious when a meditator is ready to give up sex for their meditation – they simply enjoy their meditation more. Sex thus becomes a distraction from something that is more pleasurable and more worthwhile. So a good meditator can choose the monastic life or to spend time in monasteries depending on how their practise is going in a quite simple, straightforward manner. Also, in terms of learning meditation, it is important to be able to get advice when you need it and actually equally important to avoid advice when you are doing well. This is the reason why a good monastery is more of a spiritual drop-in centre rather than somewhere that provides courses. The Buddha taught people mostly in an individual way rather than in groups for the same reason. It seems that in terms of beginners the Buddha taught almost exclusively in an individual way in order to get someone started. From then on the more a teaching is tailored to an individual the better. We all have our different abilities or obstacles in meditation and there are very many different techniques or approaches to choose from. Some approaches will work for us, others may even be harmful. Also our needs will change as time goes on, we will need to do different techniques in order to balance our minds.

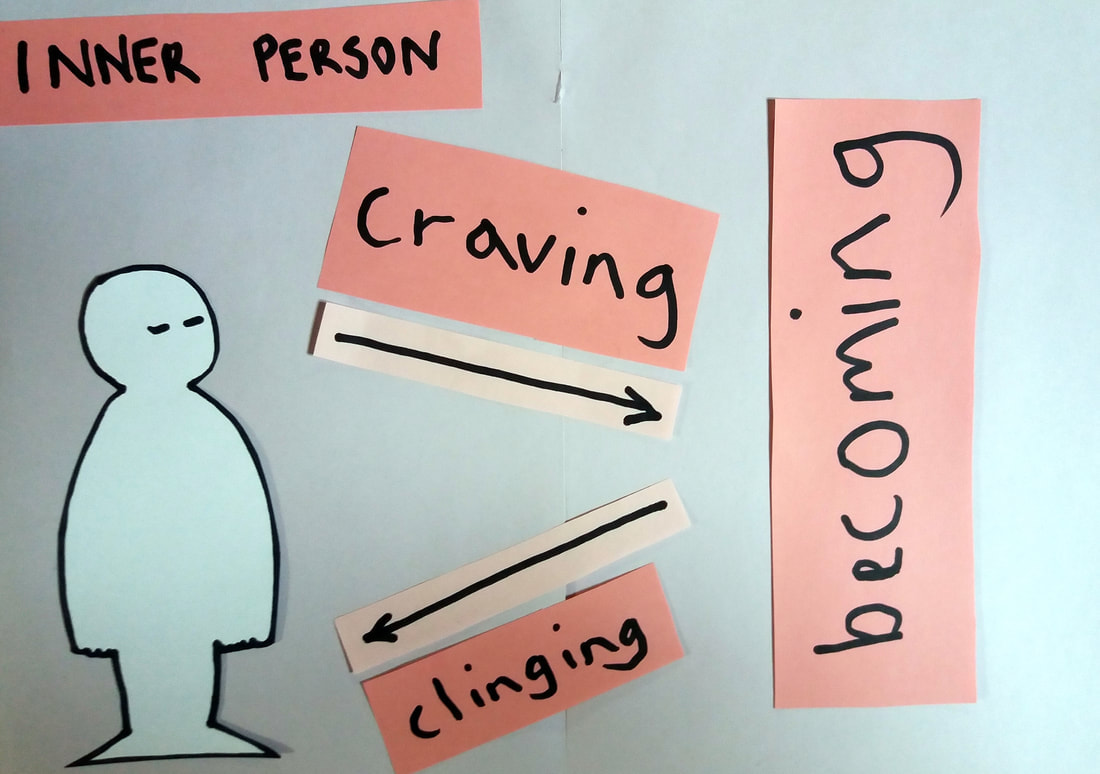

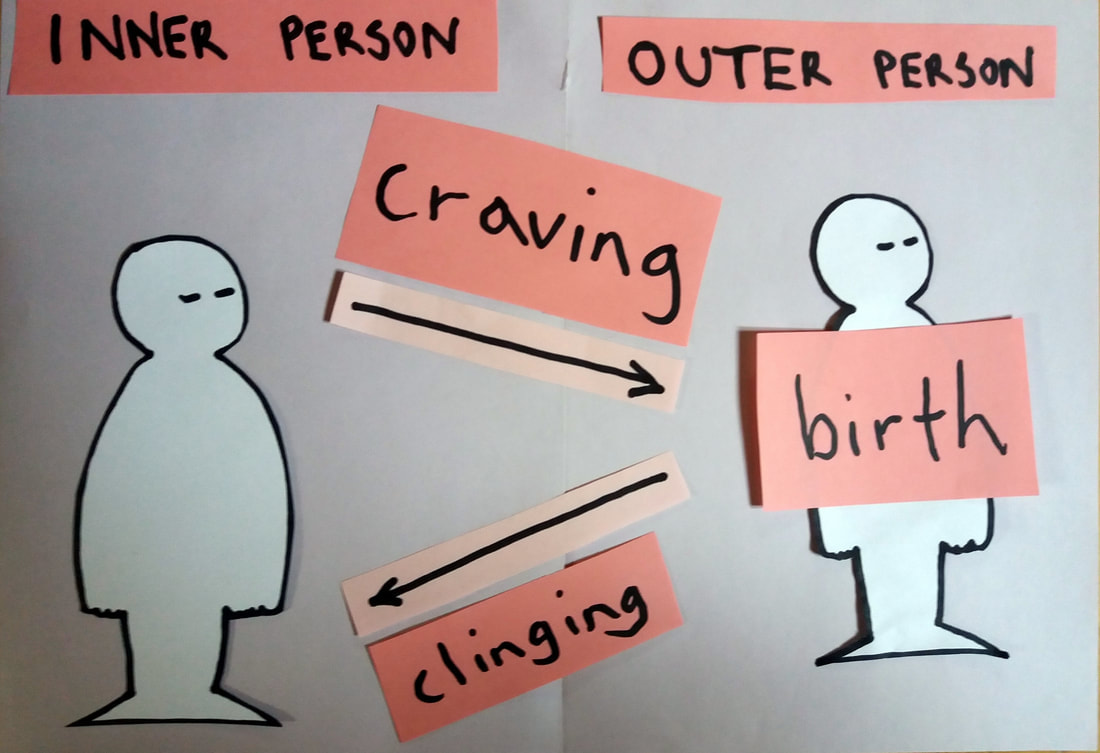

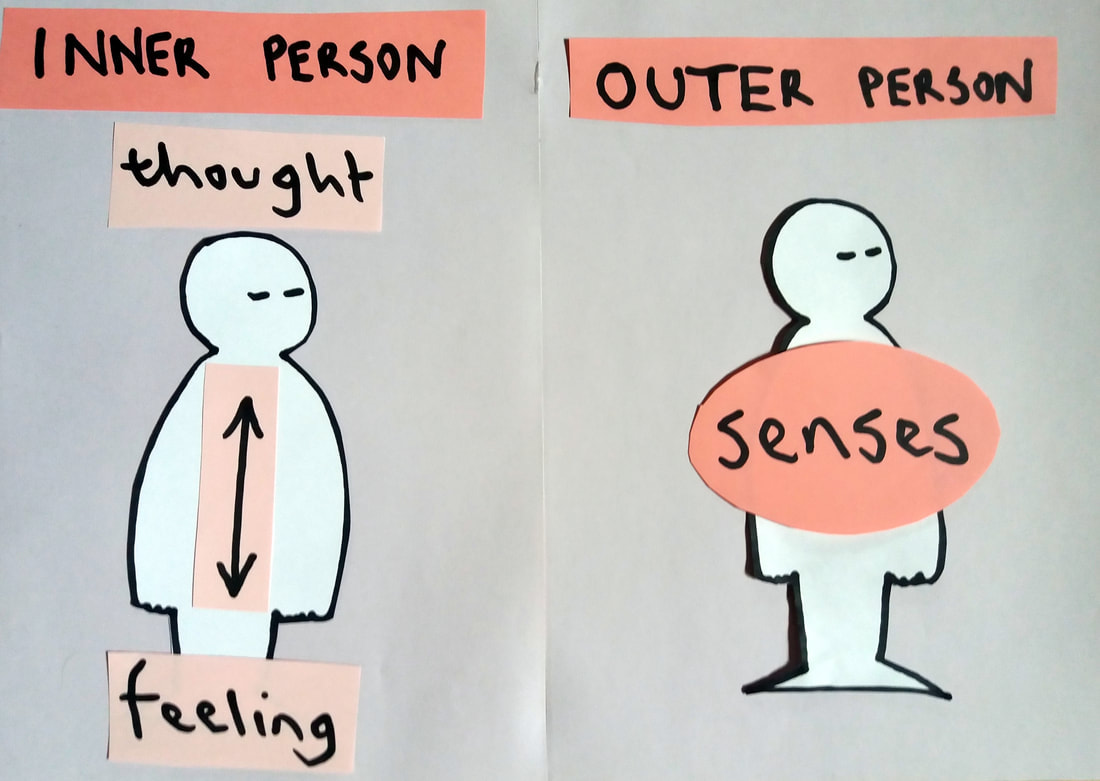

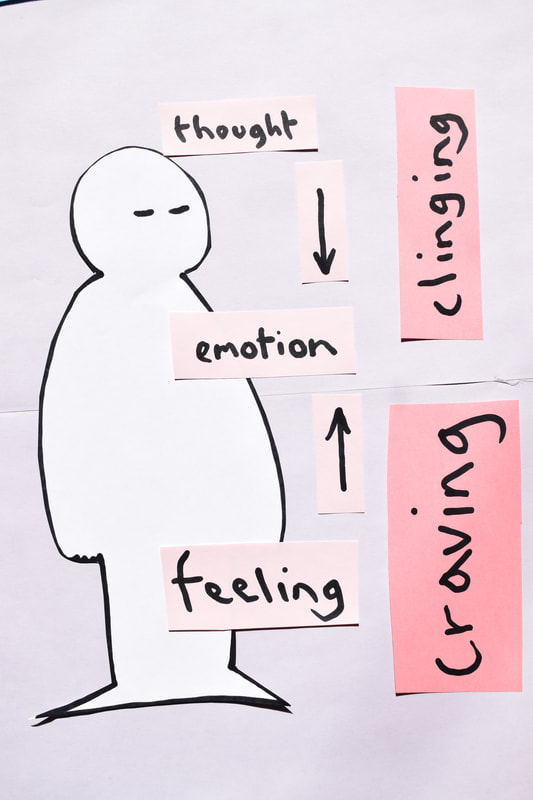

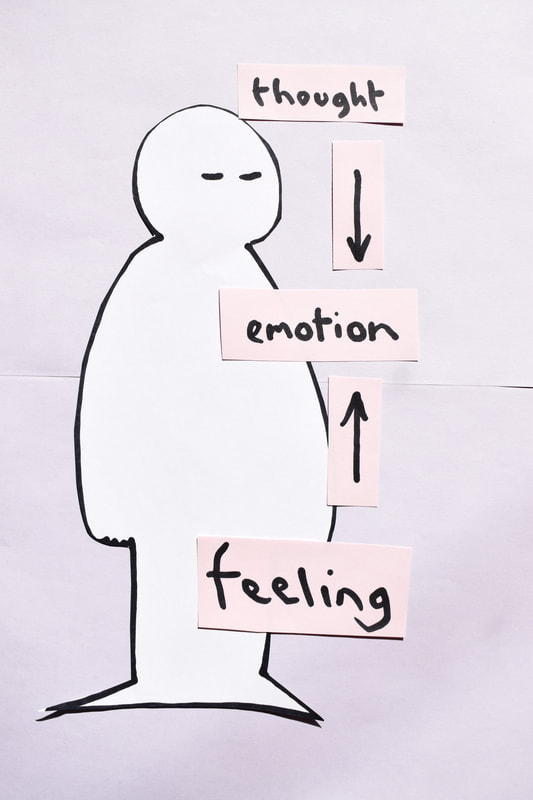

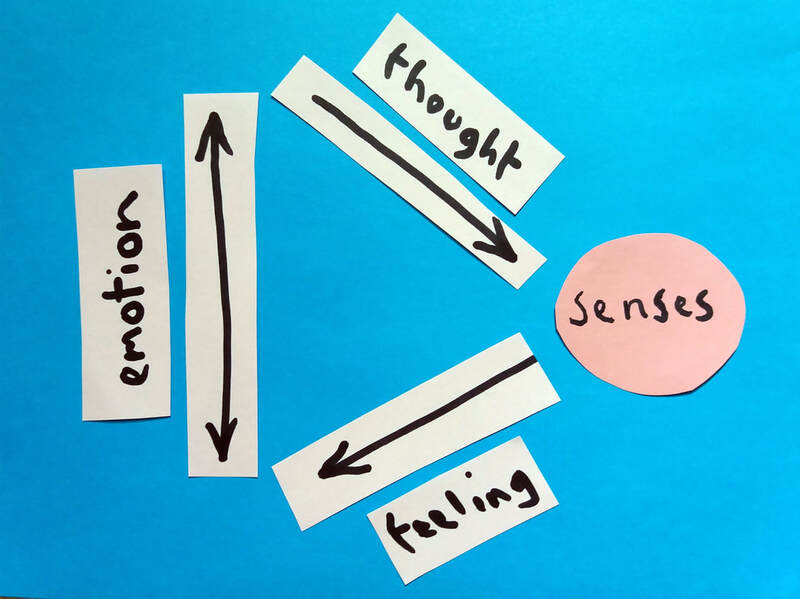

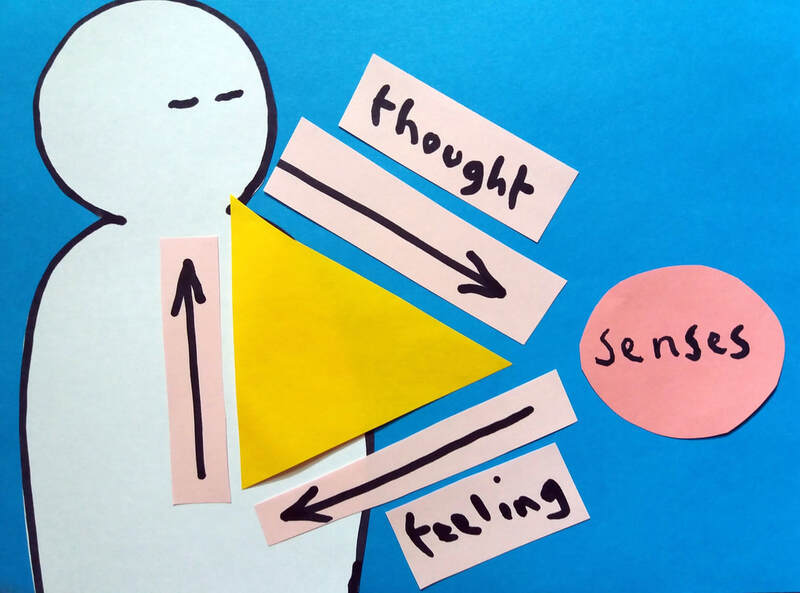

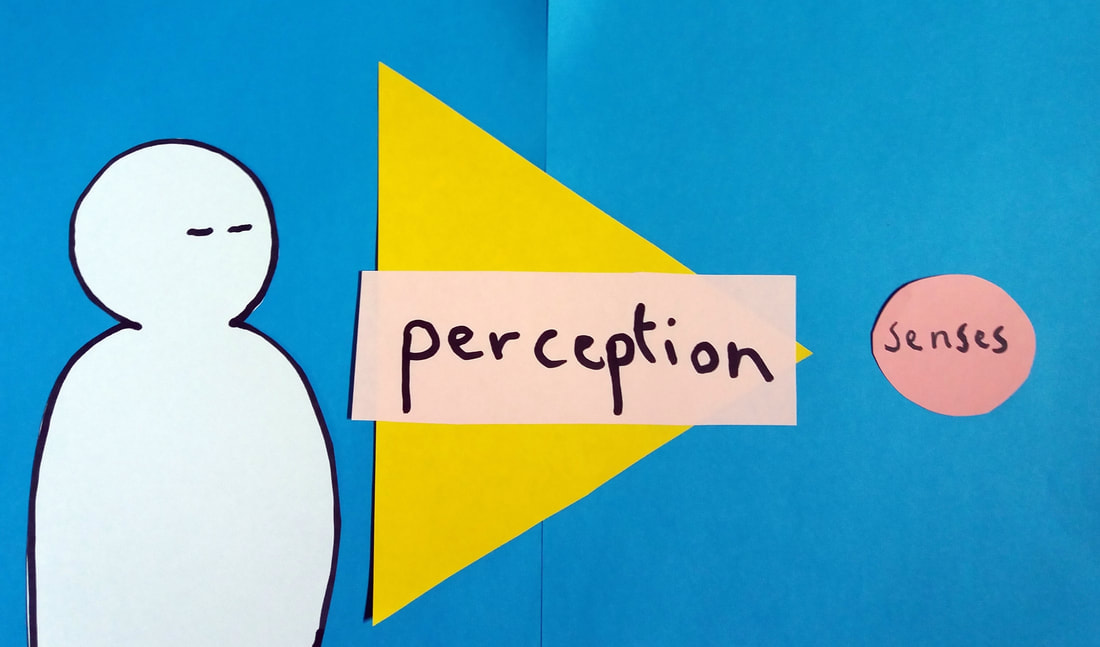

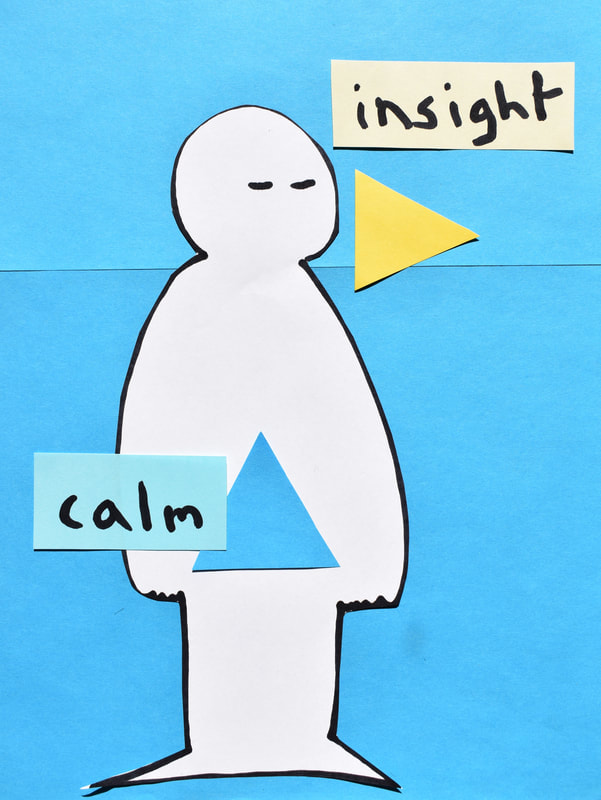

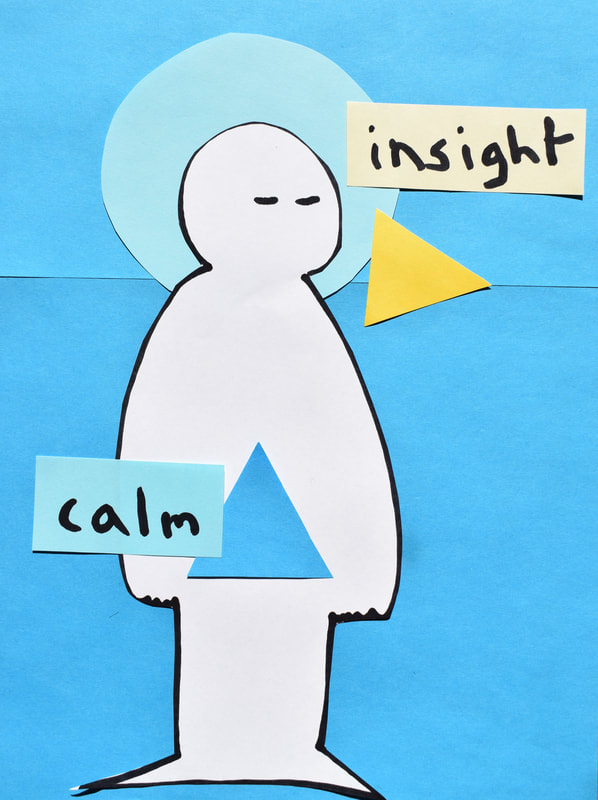

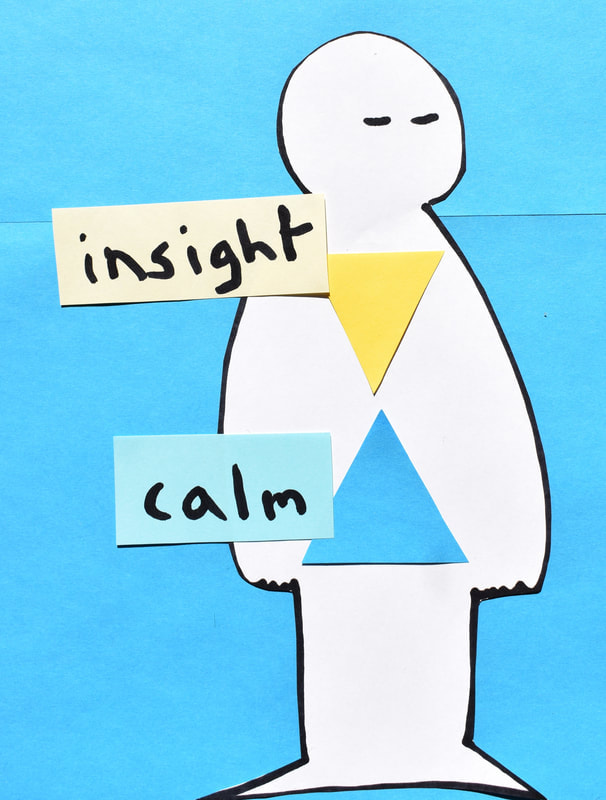

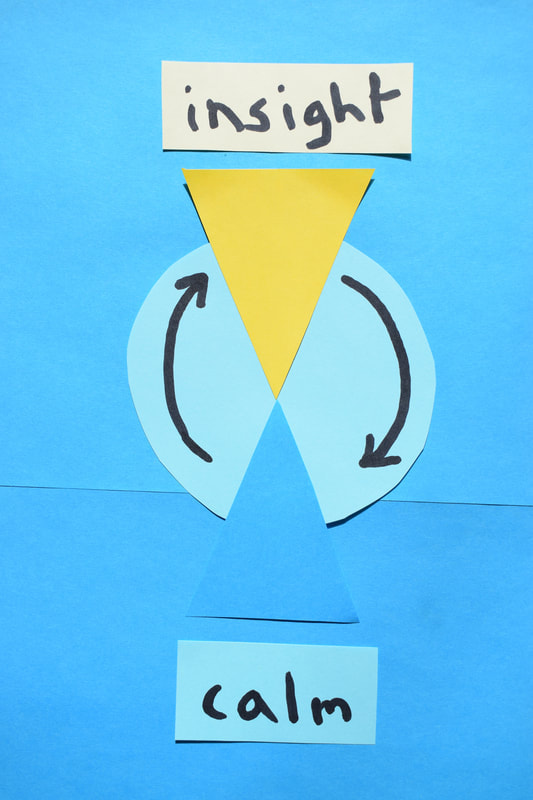

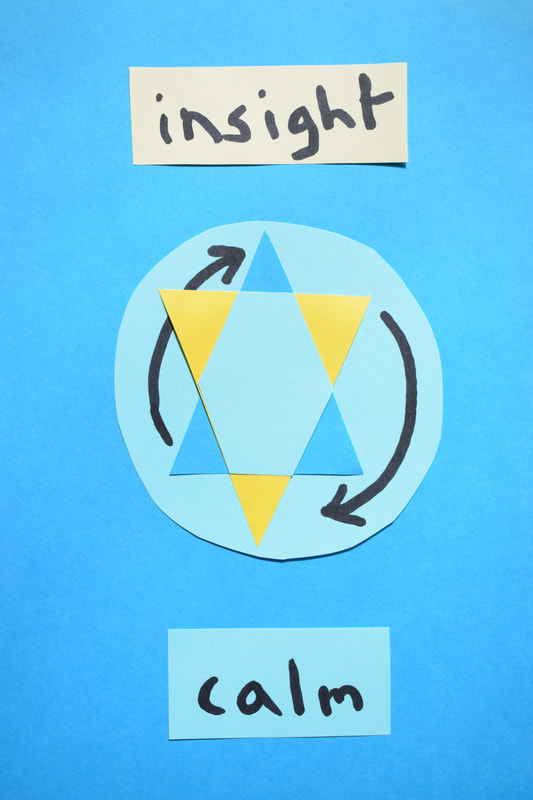

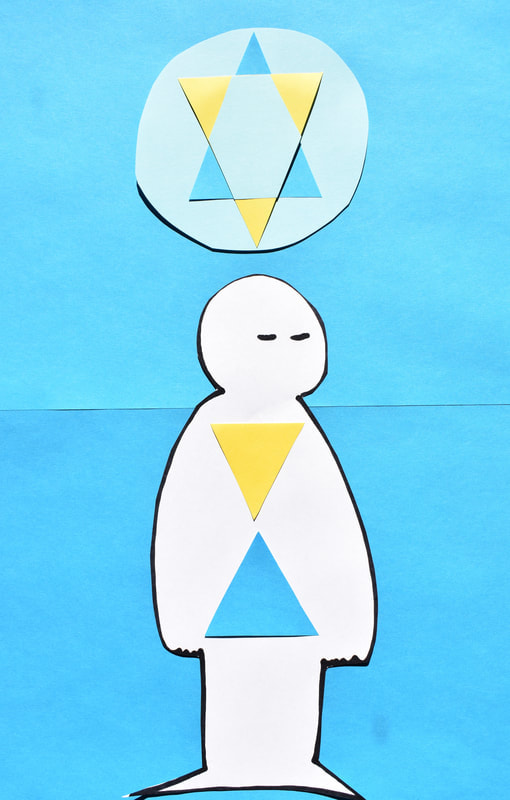

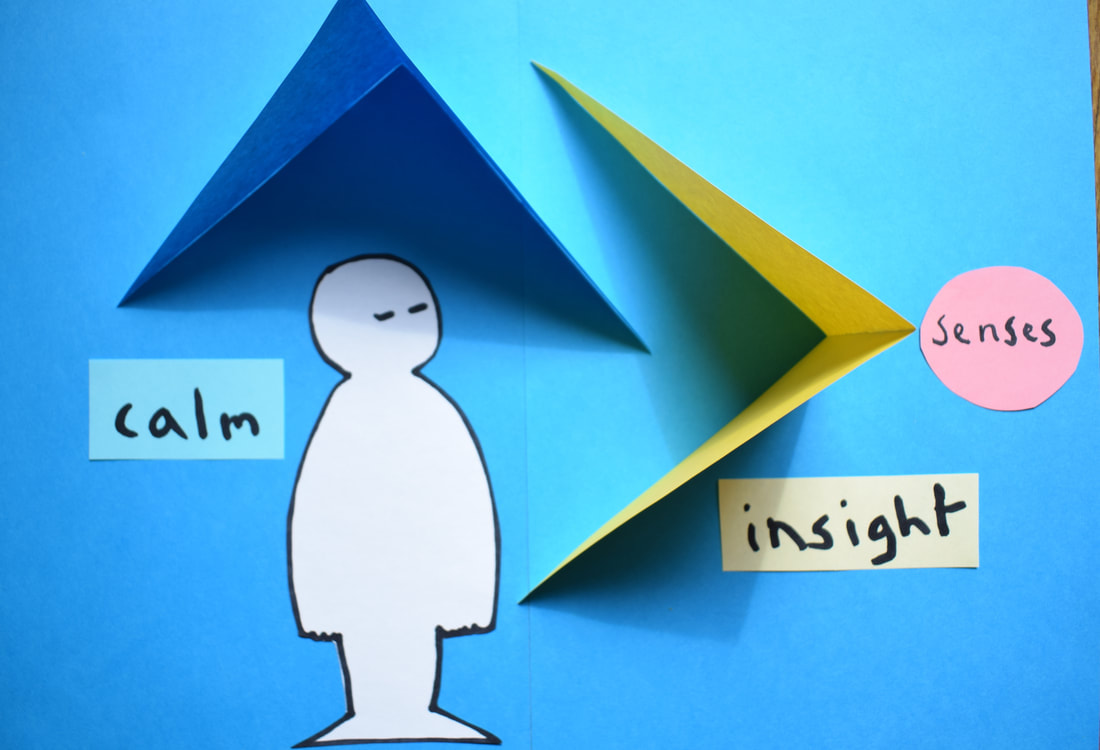

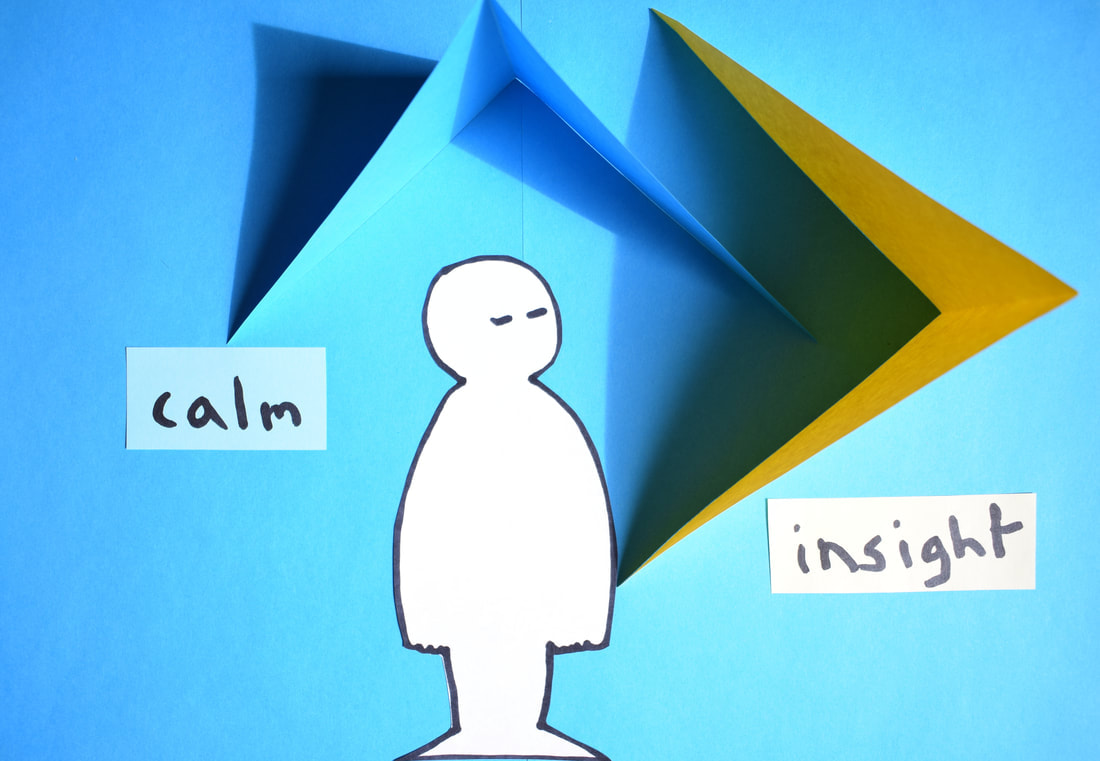

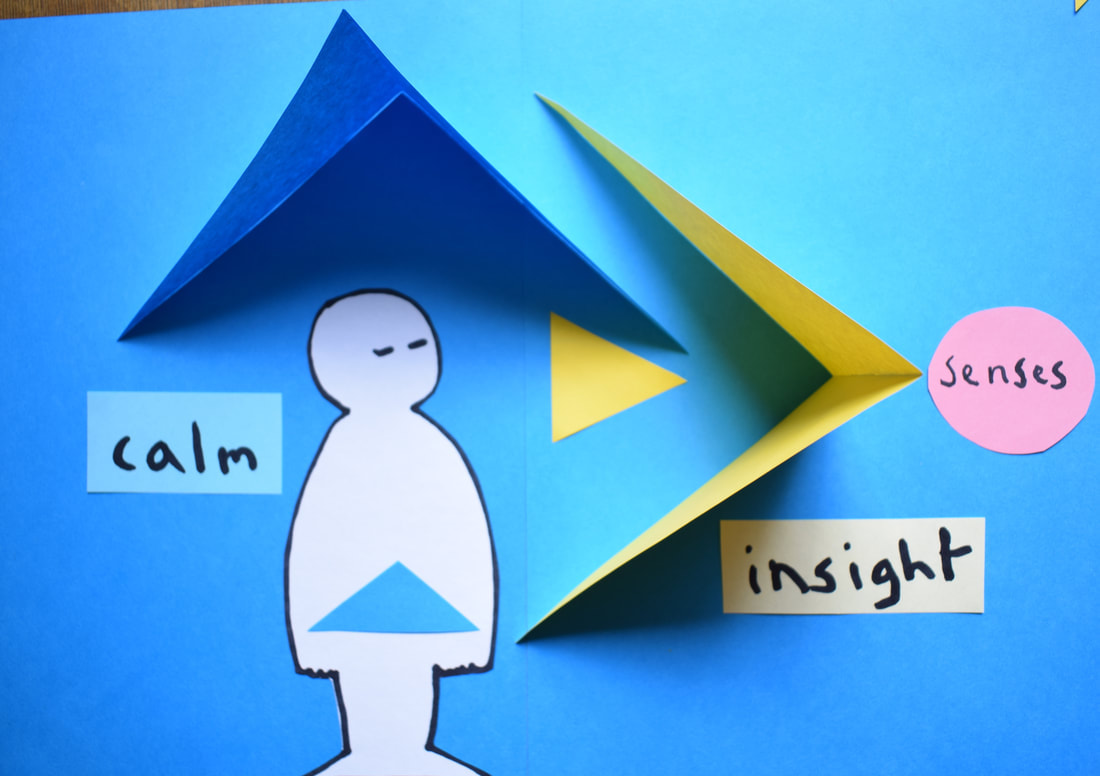

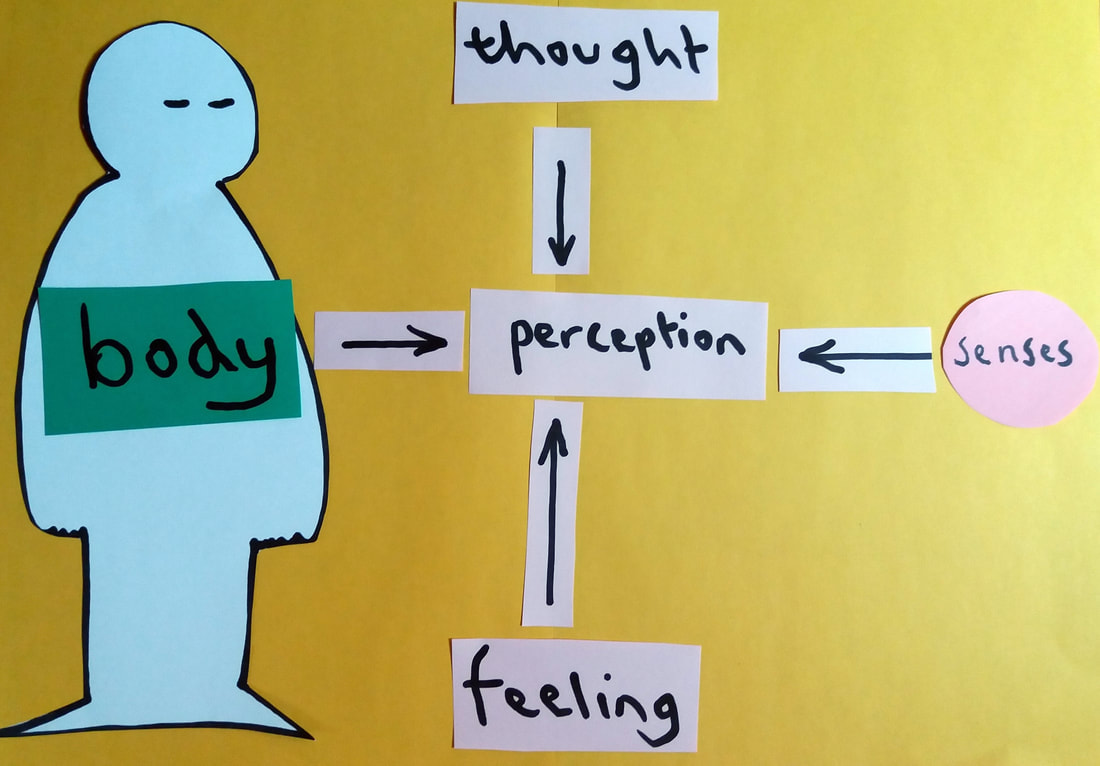

All this means that a relationship with an experienced teacher can be very valuable. Unfortunately, in contrast to this, so many teachers just give out simple, universal instruction these days and will try to convince people that theirs is the only way. This is what makes you a popular teacher and suits the propagation of the teaching by computer. It creates mass movements behind teachers that only lead to division and difference of opinion in the religion as a whole. This mass approach is also, I believe, an obstacle to spiritual community life. People hide in the group and do not really get to know each other or develop their independence as spiritual practitioners. Neither do people develop the broad approach to meditation that bears greatest fruit in the long-term. I find this all rather immature but forgivable in the relatively new tradition of Buddhism in the West. These then are all the reasons I believe in traditional monasteries as the best place to learn meditation and the reasons I have chosen to live in one. I offer this for your reflection Ajahn Kalyāno http://www.openthesky.co.uk If we sit still in the forest for long enough we naturally find our place in nature. There is no need to think. The beauty and the beast of pleasure and suffering together teach us all we need to know. And we find a balance and peace. From the beauty we see the laws of nature expressing themselves, the purity of reason reflected in the order and symmetry. We see our minds as part of a greater mind. From the beasts, from the weather and the bugs and from our own body, we learn that we are not in control. For our bodies, we know deep down, are part of nature too…. And, if we can continue to relax the body and let go, we will find the greatest of relief. We will realise how much to have tried to control had been a stress and a burden…. Going home, if we find stress calling us to again let go, we will find that if we can relax the body we can relax the mind…. And, as we relax the mind, we find that peace, order and reason return as if our heart was returning to its forest abode. Video versionThis is part 2 of the "Nature Series". 1. A walk in nature 2. Finding our place in nature 3. Hello nature 4. Our goodbye nature 5. It's never too late to love the world 6. True love for the world The diagrams below show how meditation changes the relationship between the mind, the body and the world. The development of calm (blue) and insight (yellow) is like a gradual centring of the mind first of all forming clear perceptions (mental images) of the world, secondly stepping back into the body. The diagrams are also an introduction to my other artwork where the relationship between calm and insight is portrayed in a more fluid, creative way. There was once a father who had high ambitions for his son and yet his son’s heart was taken by the working of wood and he wished to be a carpenter. The father could not accept his son’s passion, they argued and argued. Tragically for the father the son left home and did not return. Many years later the father received a package by post. Inside was a small wooden box, exquisitely made. Inside the box was a curled wood-shaving, just that. There was no note. It was clear that this was a message to the father from the son. Certainly the craftsmanship of the box showed his father that his son had mastered the craft for which he had left home but what was the message of the shaving? The traditional interpretation is that the shaving was a way of honouring the craft in and of itself over and above the result gained. The shaving expresses this very beautifully, for sure, and I think more besides. These were the days when people were still looking for deep spiritual practice and truth through such crafts. Within a patient, spiritual mind there can be the precision of the task and the emerging result of the work, creativity that listens as it works. There is also the beauty of the task itself and yet furthermore there can be the bliss of the silent, spacious mind. To me the deeper message of the shaving is the beauty of that which is left behind, what we let go of as we work, both internally and externally, that opens this space. Thus the shaving is ultimately a symbol of this letting go and of the joy and the freedom of the open mind. The bliss of such letting go makes the things we let go of the most beautiful things in the world. We do not hang on to these things either, these signs of freedom, but can offer them to others like the son to his father. The shaving and its presentation within the box is to me a statement that the beauty of letting go, of renunciation, can become the greatest prize and joy. For this is a renunciation that is not a negation of the world but is rather a growing greater than the world. This is the highest joy, of a freedom within the world, active and capable, creative within that world and also beyond the world. This freedom was, I believe, the gift that the son would have wished for his father. It was offered in a way beyond words because this very offering of truth is itself beyond words. Let us hope that the father’s love for his son led him to treasure the gift and search deeply in his mind and heart for its deepest message. Perhaps this gift can also be a message to every aspiring master of the wood that the ultimate value of the craft may be far higher, far deeper, far wider than it may have appeared to be in the beginning. I am not a carpenter but a mere contemplative. To me this story speaks of the joy and meaning of silence and space, of freedom and of resolution won by the craft of the thinker, there in the open, peaceful, creative mind and I offer you these words, these reflections as a gift with the love of a son for his father and let go. I won’t be trying to persuade you to take up carpentry. Its up to you. I offer this for your reflection Ajahn Kalyāno http://www.openthesky.co.uk This text was written as a summary of Ajahn Kalyano's teaching by George Petre, after having participated in multiple retreats with the Ajahn. The detachment of mind from the senses and sense objects, including the subtle objects of thought and emotion, is the precondition for the realisation of things as they are, the reality at the heart of every being. This requires a particular attitude when interacting with both the inner and the outer world. In the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, this approach is related to the development of attention-recollection in the present (sati), with particular emphasis on the development of this quality in relation to the body. The development of attention in the present moment hinges on the capacity of letting go of craving for sense objects and of craving for being, understanding that the latter is merely another expression of the first. The more complete the letting go, the better established the presence. And the better established the presence, the easier the letting go. This presence gradually realises itself as an openness of heart. With the knowing now turned toward being, the seeing that the two were never really separate becomes possible. Knowledge of being supplants experience through the senses. It is also here that the knowing finds independence – release and union at the same time – the emptiness of the mind in the pure emptiness of the heart. Yet, this opening of being is at the same time an opening towards the world, towards experience, towards thought and emotion. It is this opening in the presence of the body that is the key for the development of dispassion – being with experience rather than lost in experience. All experience now has the same quality – the quality of knowing. At this point, the old identification with the body has been let go of completely. It is through the contemplation of the body, contemplation of the suffering that is the result of craving and attachment to the body and the subsequent letting go of all obsessions with the body that this process is taken to completion. As the roots of the defilements – greed, hatred and delusion – are cut off the mind-heart discovers true stillness. Here also, perhaps for the first time, there arises an experience of really clear seeing, clear knowing. Clear because there is no longer the distortion of the defilements. Clear also, because this knowing is direct, no longer mediated through the senses. It is possible to say that through the practice of attention-recollection in the present, the faculty of knowing is transformed into higher knowing – the capacity to see things from the heart, the capacity to see things as they are and with this the capacity for spontaneous, unrehearsed compassion. This is true wisdom – wisdom that is not dependent on thoughts or concepts. Ajahn Kalyāno

Biographical story...

Once upon a time I was a student of anatomy. I used to have weekly classes in the morgue examining preserved specimens of parts of human bodies. One week an arm, the next week half a head...However much I tried to be scientific about it this was always a confronting, emotionally challenging experience. After every session all my colleagues went to the pub. I didn't drink and went alone back to my room to meditate. One of these days I spent a whole afternoon examining the hamstrings of a dead man's leg, playing with the different tissues to get the feel for their texture so that I could feel for the different structures under the skin of a live patient. This was my most intimate contact so far. I left the session feeling strange, disoriented. As I was walking along the street on my way home I felt my own legs underneath me and to my complete surprise a perfect image arose of the inside of one of my legs, like x-ray vision. I saw my hamstrings working bathed in the most sublime, cool light. For a moment I felt an enormous sense of lightness and freedom. I had never felt happier yet I knew not why. That moment changed my life. A part of me, a part that has grown and grown, has been looking for that sense of freedom ever since. Biographical story...

Many years ago as a layman I was travelling in the south of Chile. One full moon night I had a very powerful, lucid dream where I was kneeling down, sick and covered in warts and my Dhamma teacher at that time, Ajahn Sumedho, appeared and cured me with a great blast of light. The following morning I was walking along with my Chilean companion. I had a wart on my hand that had been there almost two years. I had a habit of scratching it but as I began to do this, remembering the dream of the night before, it immediately came off. I was completely stunned and stood there looking at my companion who began to smile. Before I could tell her about the dream she began to tell me how in the night she had taken some threads from my shirt and buried them in the ground, saying an ancient magic spell. She knew me and my scientific background and was pleased to be able to show me there may be more to life than I might have thought. But all I could think about was Ajahn Sumedho. Many years later as a monk I was able to tell Ajahn Sumedho the story. He laughed out laud and said, jokingly, "Yes Kalyano, at night I fly around the world curing people of their warts." I could not seem to get him to take the story seriously but the fact was that the dream and the period that followed had felt like some kind of deep healing and had, in addition, opened up my whole view of the world. It was one of the reasons I had ordained with him as a monk, for the magic. |

Categories

All

|

Open The Sky - Reflective and creative work by Ajahn Kalyano